Innovating Together

Ambition and Innovation: Charting the Future of UK Tech Transfer and Commercialisation

Ambition aptly characterises the current appetite across the UK tech transfer ecosystem. Leaders from government, industry, and research sectors, impressed by the UK’s world-class science and research capabilities, are hopeful and excited about the potential for domestic research to evolve into a powerhouse sector driving national economic growth. Yet, there is an urgent call for a comprehensive innovation framework that can facilitate this ambitious trajectory, with the capacity to nurture the growth and development of companies poised to become world-class, globally impactful players.

The UK’s Modern Industrial Strategy 2025 represents a laudable step forward, providing a structure for fostering innovation through collaboration and resource pooling. It outlines the government’s commitment to advancing innovation, improving regulatory speed and efficiency, attracting global talent, enhancing the investment mandate of the British Business Bank (BBB), and mobilising pension fund investments. Nevertheless, faster and more decisive action is needed to unlock the full capabilities of the UK’s research and innovation sector.

To contribute to the ongoing discussion, WittKieffer’s recent article, Cultivating Tech Transfer: The UK’s Next Frontier, explored the evolution, current opportunities, and pressing challenges within the UK tech transfer landscape. Providing an in-depth look at the evolution of UK tech transfer, it examined the many factors that distinguish innovation and its development in the UK from more mature markets, such as the US, to identify adaptable lessons while advocating for a tailored approach. The report posited that leadership is a decisive factor for tech transfer in the UK as it seeks to develop a fully-fledged innovation value chain capable of transforming promising ventures into market leaders.

Building on this foundation, Innovating Together dives into how the UK can secure sustained growth and deliver meaningful economic and societal impact. By facilitating discussions between academia, biotech, investors, and other major stakeholders, this piece presents key considerations for leaders across the innovation spectrum. We invited leaders with expertise in commercialisation and innovation scaling to share their success stories and lessons learned to illustrate the pathways to achieving ambitious goals for establishing the UK as a global innovation powerhouse.

Considerations for the Tech Transfer Crossroads

The notably multifaceted and complex nature of tech transfer in the UK is unique; unlike the US with its deep capital markets and substantial government funding, or China with its centralised innovation directives, the UK developed a distinctive collaborative ecosystem in response to resource constraints. The depth and breadth of stakeholders involved in the UK ecosystem — from universities to venture capital (VC) funds, government, and the broader startup community — incentivise an interdisciplinary approach to competing globally, which would benefit from even greater connections among this continuum. This diversity, however, also presents challenges as each group of participants focuses on different stages of development, bringing unique priorities and objectives alongside more universal goals. This heterogeneity can complicate efforts to establish a cohesive and efficient innovation environment; but if better coordinated, it could significantly support the desired policy objectives.

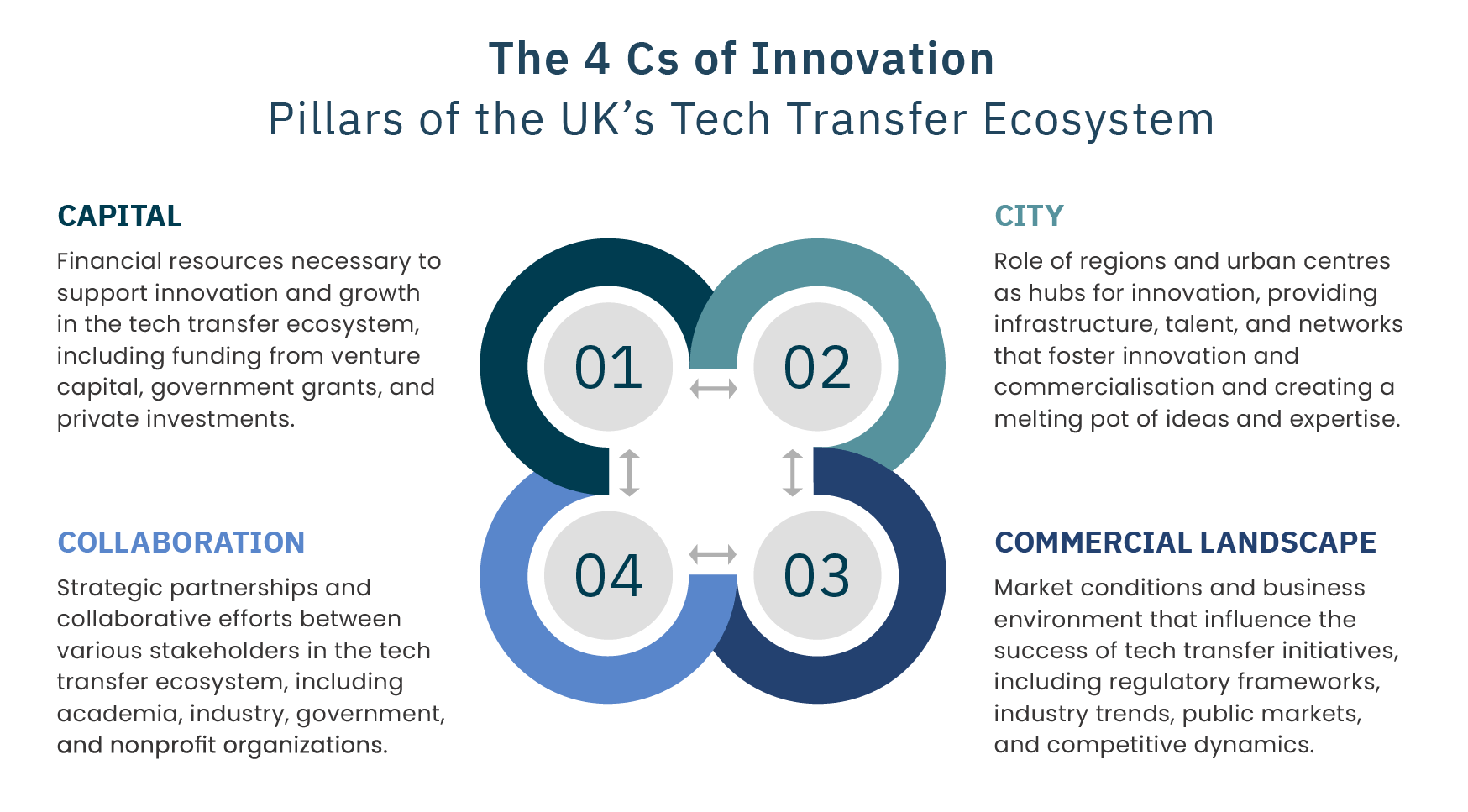

To navigate these complexities, we designed a framework to provide a structured approach to addressing the various challenges and opportunities within the UK’s tech transfer ecosystem. This framework, which we call the “4 Cs,” identifies four key considerations that are imperative for understanding and advancing the ecosystem: Capital, City, Commercial Landscape, and Collaboration.

#1. Capital

In 2023, the UK saw a significant and useful development in supporting VC funding for university tech transfer with the release of the University Spinout Investment Term (USIT) guide. This collaborative effort between prominent VC investors and leading universities aims to streamline investment negotiations, establish a framework for positive deals, and foster collaboration between tech transfer offices (TTOs) and VC firms.

The USIT guide has been well-received but still requires broader adoption across UK universities. To advance, the sector requires a more comprehensive strategy for connecting VC funds with university spinouts and linking growing businesses with capital through and beyond the seed stage. This includes proof-of-concept (PoC) funding, seed funding, and early- to mid-stage venture capital to support technologies through clinical development.

Currently, many large VC funds focus only on clinical-stage assets, leaving a void for early-stage ventures. Strategic investment is critical to ensure promising technologies successfully progress to clinical development. Early-stage spinouts face challenges in securing competitive financing, highlighting the need for comprehensive support for entrepreneurs seeking funding across different commercialisation stages.

Investment in tech transfer has historically been challenging, but interest from private capital has grown, as evidenced by key developments such as the launch of Oxford Science Enterprises (OSE) in 2015. Building on its partnership with UCL, UK venture firm AlbionVC is expanding its university-venturing scope to back high-potential spinouts from academic and research institutions across London.

More significant PoC funding prior to scale-up VC investment is needed. Historically, funding via impact acceleration accounts (IAAs) and the UK Research and Innovation’s PoC fund has been useful but could be more impactful if expanded. This funding should focus on meeting pre-commercialisation milestones that align with industry standards and market needs rather than purely academic objectives. While the US benefits from robust university-affiliated incubators and accelerators and endowment investments in venture capital, the UK would benefit from developing its own approach to expanding comprehensive on-campus incubation facilities and creating stronger connections between capital and company formation. Attracting top-tier talent from the outset is also vital, as VC firms are more likely to invest in teams with proven expertise. This approach has the potential to enhance the transformation of early innovation into viable spinout companies with strong PoC to industry standards, significantly boosting its value to investors and therefore the possibility of raising further funds to propel commercialisation.

Research-intensive universities in the UK fund and manage a cohort of top prospects towards spinout, providing targeted support and resources. This approach prioritises projects with the highest potential for societal impact and commercial success. Other research organisations like the Francis Crick Institute, supported by Cancer Research UK, provide ring-fenced innovation funds dedicated to accelerating the translation of discoveries into societal benefit.

The demand for connecting investors with impactful researchers is shared between TTOs and VC funds, and a greater focus on fostering these interactions would encourage further private investment.

#2. City

UK tech transfer faces challenges nationwide. Historically, there has been a focus on the so-called “Golden Triangle” — composed of Cambridge, Oxford, and the research-intensive London universities — due to the high number of spinouts emerging from these hubs. This concentration created a self-reinforcing ecosystem where success attracts more investment, talent, and infrastructure, leading to even greater access to funding in these regions.

Recent initiatives mark a shift from regionalisation bias to geographic diversification, addressing the need to both harness innovation nationwide and efficiently allocate resources. Data shows notable spinout growth in regions with research-intensive universities like Edinburgh, Manchester, and Belfast. These emerging centres require targeted support tailored to their specific development stages, financing levels, and infrastructure needs. Such customised approaches maximise economic impact by engaging local stakeholders and unlocking previously untapped research potential.

While regions outside the Golden Triangle possess substantial research capabilities, they often lack adequate facilities and face seed capital shortages despite positive growth indicators. Recognising this disparity, four innovation hubs in Merseyside, East Anglia, the Midlands, and Northeast England will receive £30 million in backing to grow more spinouts.

Meanwhile, established innovation centres face different challenges. London’s tech transfer ecosystem struggles with post-seed round capital and physical lab capacity. Oxford and Cambridge face housing shortages and transport link issues, which universities are actively addressing. Queen Mary University of London’s life sciences campus in Whitechapel and Oxford’s innovation district, Oxford North, are ambitious initiatives requiring planning support and capital.

The UK’s innovation landscape requires solutions as diverse as its regional challenges. The varying maturity levels across innovation centres must inform all policy and investment decisions, as a one-size-fits-all approach will not suffice. Emerging hubs may need moreinitial investment to build infrastructure and attract seed capital, while established centres might focus on expanding post-seed funding and improving physical infrastructure. This full spectrum of needs must be addressed if the UK is to have a thriving tech transfer system where there are no geographical boundaries on harnessing research potential, and the benefits are shared nationwide.

#3. Commercial Landscape

One of the most pressing challenges facing UK tech transfer is the broader environment for commercialisation, with difficulties abounding for companies looking to scale. These multifaceted barriers include insufficient manufacturing capabilities, a shortage of experienced C-suite talent, inadequate growth-stage funding, the absence of a pan-European public equity market, and a comparatively shallow capital pool and investor base compared to the US. The current state of the London stock market further complicates matters, making UK IPOs less viable exit routes.

The regulatory framework for drug approval and clinical trials represents another critical dimension of the commercial landscape. Establishing dedicated trial centres that leverage the UK’s NHS data infrastructure could create a competitive advantage for UK-based companies. Additionally, implementing advantageous pricing windows during initial commercialisation periods would help UK-formed companies compete globally during their most vulnerable growth phase.

Leadership development is crucial for the UK’s evolution into a complete innovation economy that supports companies throughout their lifecycle. The relative immaturity of the entrepreneurial sector has far-reaching consequences, as experienced leaders prove essential in guiding companies through crucial growth milestones. While post-Brexit talent shortages created challenges across all employment levels, there is growing optimism about talent returning to the UK. The government’s commitment to attract global expertise, as outlined in the Modern Industrial Strategy 2025, is welcome but requires more aggressive incentives to position the UK as the premier destination for ambitious startup leaders. These can include tax relief on stock and reduced tax rates on incentive compensation earned during scale-up periods, enhanced immigration pathways, and addressing the compensation culture gap that exists between the UK and other innovation hubs.

Similarly, the strategy could benefit from bolder initiatives and fresh perspectives addressing the lack of manufacturing incentives and scale. The UK has lost significant traditional medicines manufacturing capability over the last two decades, with 7,000 jobs and a 29% production volume decline since 2009. This manufacturing erosion was recently exacerbated by significant withdrawals, including Merck & Co. pulling out its planned £1 billion R&D centre in London while discontinuing all UK research operations, and AstraZeneca scrapping plans for a £450 million vaccine manufacturing expansion in Merseyside due to reduced government support.

Data represents an under-leveraged asset in the UK innovation landscape. The government’s recognition of data as an economic asset creates pivotal opportunities for TTOs and spinouts. Structured, FAIR datasets can dramatically reduce validation timelines and de-risk early ventures. By driving collaborative data-sharing between universities, government, and industry, the UK can accelerate discovery and build globally competitive spinouts.

Current metrics emphasising spinout quantity rather than quality have led to a proliferation of smaller ventures competing for limited capital. A strategic shift toward high-impact spinouts, regardless of quantity, would better attract significant investment and experienced leadership. Companies must be founded with scalability in mind, establishing credible leadership teams, securing adequate capital, and forming robust syndicates to attract growth funding. This requires milestone-based leadership development, ensuring teams evolve appropriately as companies grow.

In an attempt to bridge the commercialisation gap, in March 2025, the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee launched an inquiry into financing and scaling UK science and technology, focusing on innovation, investment, and industry. The inquiry addresses many issues outlined in this article, including a lack of later-stage investment and international comparisons in scaling up, representing an awareness of the primary issues the market is grappling with.

#4. Collaboration

In the global arena, the UK lacks the scale and resources found in markets like the US and China. Therefore, collaboration within the UK is essential for the country to compete effectively in terms of the economic and societal impact of its spinouts. To this end, the sector is increasingly ready to embrace this collaborative approach. Various initiatives serve as catalysts for syndication and collaboration, promoting the creation of companies that span multiple universities.

Corporate-university partnerships represent another critical dimension of collaboration that requires strengthening. These partnerships can provide universities with industry expertise, market insights, and commercialisation pathways while giving corporations access to cutting-edge research and innovation. Developing structured programs that incentivise joint R&D projects, shared facilities, and talent exchange between industry and academia would accelerate the translation of research into commercial applications. The “lab-to-market” infrastructure grant scheme could specifically target these collaborative ventures, bridging the gap between academic discovery and industrial application.

We are witnessing a significant shift towards more cross-regional collaborations and initiatives, such as the UK Innovation Corridor, Oxford-Cambridge Innovation, and the Innovation Partnership between Greater Manchester and Cambridge. This marks a transformative change in mindset from rivalry to partnership, fostering a more unified approach to innovation.

Beyond collaboration through funding, leaders are advocating for universities to collaborate in raising capital, sharing networks and expertise, and aligning IP. By sharing these critical assets, universities can adopt a more integrated and synergistic approach to innovation. This level of partnership is essential for creating an environment where groundbreaking ideas can flourish and be transformed into successful enterprises. With this collaborative spirit, the UK is poised to develop its own tech giants, akin to Apple or Microsoft.

While public markets remain important, a united front between TTOs at universities and across the entire innovation ecosystem will be crucial for achieving the anticipated success of the UK spinout economy.

The UK’s Innovation Imperative

While the UK boasts some of the world’s best universities, there is an urgent need to address the financial, infrastructure, and talent-related constraints that hinder growth and find ways to attract and retain talent and investment domestically. This requires a decisive shift from lamenting the challenges to taking bold actions that foster an environment conducive to innovation. Although innovative ideas abound, the availability of capital remains limited, necessitating strategic investment to harness these opportunities.

The following recommendations emerge from our discussions with key stakeholders across academia, venture capital, industry, and nonprofit. They outline potential pathways to strengthen the UK innovation landscape, acknowledging the diverse perspectives and priorities that exist among stakeholders.

Bridge the pre-commercialisation funding gap. Create a significant fund for post-academic/pre-commercialisation de-risking of research prior to spinout investment. This critical bottleneck requires substantial investment to transform promising research into investable technologies.

Unlock scale-up capital through financial innovation. Rather than establishing centralised bureaucratic structures, focus on commercial and financial mechanisms to unlock scale-up capital. Ongoing reforms require acceleration and clear exit pathways, potentially through revitalised public markets.

Develop targeted entrepreneur incentives. Create compelling incentives to attract and retain entrepreneurial talent. These should focus on making the UK the premier destination for ambitious startup leaders through tax advantages, visa pathways, and support structures that compete globally for top talent.

Cultivate cross-university IP syndication. Support regional initiatives that pool IP across multiple institutions. These efforts require sustainable financial models and sufficient scale to attract significant investment, potentially through public-private partnerships that de-risk early-stage capital deployment.

Reform public sector procurement. Enable public sector organisations to function as risk-based early customers for innovative startups. The COVID Vaccine Taskforce demonstrated how streamlined, risk-tolerant procurement can accelerate innovation adoption.

Shift quality metrics beyond spinout numbers. Move beyond simple spinout quantity as a success metric toward quality-focused evaluation frameworks. This shift requires leadership from government, universities, and investors to emphasise long-term impact, sustainability, and growth potential rather than transaction volume.

Strengthen early-stage leadership pipelines. Address the critical shortage of experienced early-stage CEOs and CFOs who can partner effectively with academic founders. This requires targeted development programs, international recruitment strategies, and compensation structures that compete globally for entrepreneurial talent.

Coordinate accelerator ecosystems. Develop a more coordinated approach to the proliferation of accelerators to reduce fragmentation and duplication. This should include sector specialisation, clear market failure identification, and strategic deployment of public funding to complement rather than compete with private initiatives.

Create incentives to bring back manufacturing and commercial corporate partners. Implement targeted incentives to rebuild the UK’s eroding manufacturing capabilities and attract corporate partners to the innovation ecosystem. This could include tax relief for capital investments in manufacturing facilities, streamlined regulatory pathways for new therapeutic modalities, and matching grant programs similar to successful international models.

These recommendations are a snapshot of ongoing conversations, not a final consensus. Each stakeholder group brings a unique viewpoint shaped by their role in the innovation ecosystem. We share these ideas to spark further dialogue and collaborative action, understanding that effective solutions will evolve through continued refinement and adaptation to regional and sectoral needs.

As we wrap up, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the contributors who shared their in-depth insights and experiences. Their expertise significantly enriched this article, helping to illuminate the pathways to achieving our shared goals of establishing the UK as a global innovation powerhouse. We extend special thanks to:

- Prof. Chas Bountra, Pro-Vice Chancellor for Innovation at the University of Oxford

- Dr. Phil Clare, Chief Executive Officer at Queen Mary Innovation, Queen Mary University of London

- Dr. Simon Goldman, Partner at AlbionVC

- James Gregson, Partner and UK Life Sciences and Healthcare Industry Lead at Deloitte

- Alex Leech, Partner in Biovelocita Strategy at Sofinnova Partners

- Prof. Gino Martini, Chief Executive Officer at Precision Health Technologies Accelerator, University of Birmingham

- Andrew Miles, Chief Business Officer at Our Future Health

- Prof. Geraint Rees, Vice Provost for Research, Innovation, and Global Engagement at University College London

- Dr. Mike Romanos, Associate Dean for Enterprise at the Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London

- Dr. Jason Slingsby, Chief Executive Officer at Tozaro

Your contributions have been instrumental in shaping the vision and depth of this work. Thank you.