Cultivating Tech Transfer Leadership: The UK’s Next Frontier

The UK’s Tech Transfer Journey at a Crossroads

Tech transfer and commercialisation of foundational research are now integral parts of the United Kingdom’s innovation ecosystem. Started in the 1980s as peripheral activities of universities, nowadays these functions drive significant advancements in the life sciences and biomedical industries while contributing to the development of breakthrough therapies. With a 70% increase in active university spinouts from 2014/15 to 2022/23 (Universities UK, 2025), the UK now stands at a decisive moment in determining how to commercialise innovation at scale.

The dynamic innovation commercialisation sector is shaped by scientific discoveries, shifts in funding pathways and priorities, and evolving government policies. However, several substantial challenges threaten to limit its full potential: a persistent talent gap in commercial leadership, particularly for scaling companies; a risk-averse culture in comparison to more mature innovation environments; limited access to growth capital beyond early stages; and the geographic concentration of success within the Golden Triangle of Oxford, Cambridge, and London. These factors collectively raise important questions about the future trajectory of UK tech transfer.

Drawing on WittKieffer’s extensive experience across the biomedical innovation ecosystem and insights gathered through conversations with tech transfer leaders at Imperial College London, University of St Andrews, and University of Cambridge, this article explores the evolution, current opportunities, and pressing challenges within the UK tech transfer landscape. We examine the structural and cultural factors that distinguish the UK innovation architecture from more mature markets like the United States — not to advocate for simple replication but to identify adaptable lessons that respect the UK’s unique context.

Leadership is a decisive factor as the UK seeks to transform into a complete innovation value chain capable of scaling companies through to full market impact and economic value creation. In response to current leadership challenges, we offer practical recommendations for UK universities seeking to attract, retain, and cultivate their talent pool. The strategic choices made by universities, policymakers, investors, and industry partners today will ensure sustained growth and meaningful economic and societal impact, alongside shaping the UK’s position in the global innovation community for years to come.

The Evolving Topography of UK Tech Transfer

Foundational academic research is essential to the broader UK innovation ecosystem, serving as the bedrock for many therapeutic breakthroughs and generating new knowledge and technologies that could revolutionise healthcare. Given this research’s potential to dramatically improve quality of life, connecting academic breakthroughs with commercial pathways is essential to accelerate real-world impact.

Tech Transfer Offices (TTOs) at universities exist to facilitate the commercialisation of foundational research in order to maximise impact and reach. Initially focused primarily on licensing activities and patent management, their functions expanded to encompass startups, spinouts, and other entrepreneurial activities. Evolving responsibilities of TTOs include safeguarding intellectual property (IP), managing incubation, creating revenue streams, attracting talent, and fostering collaboration and strategic partnerships between academia and industry. Furthermore, TTOs now play a fundamental role in encouraging innovation, entrepreneurship, and commercially-minded research on a university-wide scale, and are today a pivotal component of universities’ financial strategies, research planning, talent attraction, and student value propositions.

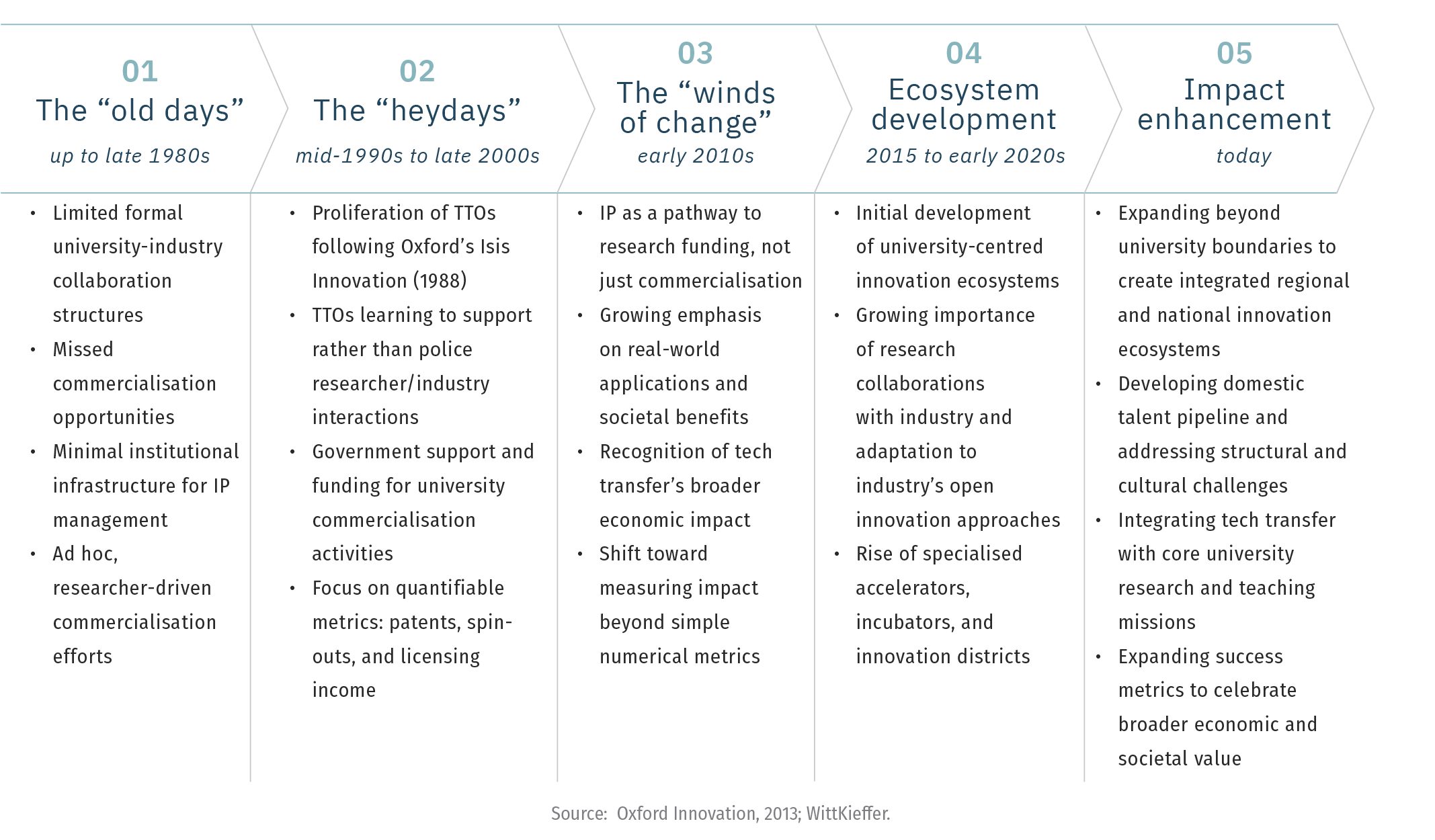

In 2013, Isis Innovation (now Oxford University Innovation) defined multiple distinct phases in developing and evolving the UK tech transfer architecture (Oxford Innovation, 2013). Building upon this original framework, which provided insights into the historical development through late 2013, we expanded and updated the phases of tech transfer evolution in the UK. Our extended model reflects how the landscape transformed dramatically in the recent decade and captures the increasingly complex role that university tech transfer plays in driving innovation and delivering broader societal impact.

The Five-Phase Evolution of University Tech Transfer in the UK

Phase one, the “old days,” spanned until the 1980s, during which commercialisation only occurred on a small scale, either between university researchers and their former students transitioned to industry, or, in a small number of cases, between industry-funded research groups within universities. Phase two, the “heydays,” from the 1990s to the late 2000s, was marked by the creation of TTOs, increased interactions between academia and industry, and a growing recognition among academic researchers of the value of IP. Phase three, the “winds of change,” began in the early 2010s as TTOs matured, developing more organised and professional project management processes and staff learning and development programmes. The global financial crisis impacted funding availability, prompting TTOs to experiment with various approaches to adapt to the evolving economic and research environment.

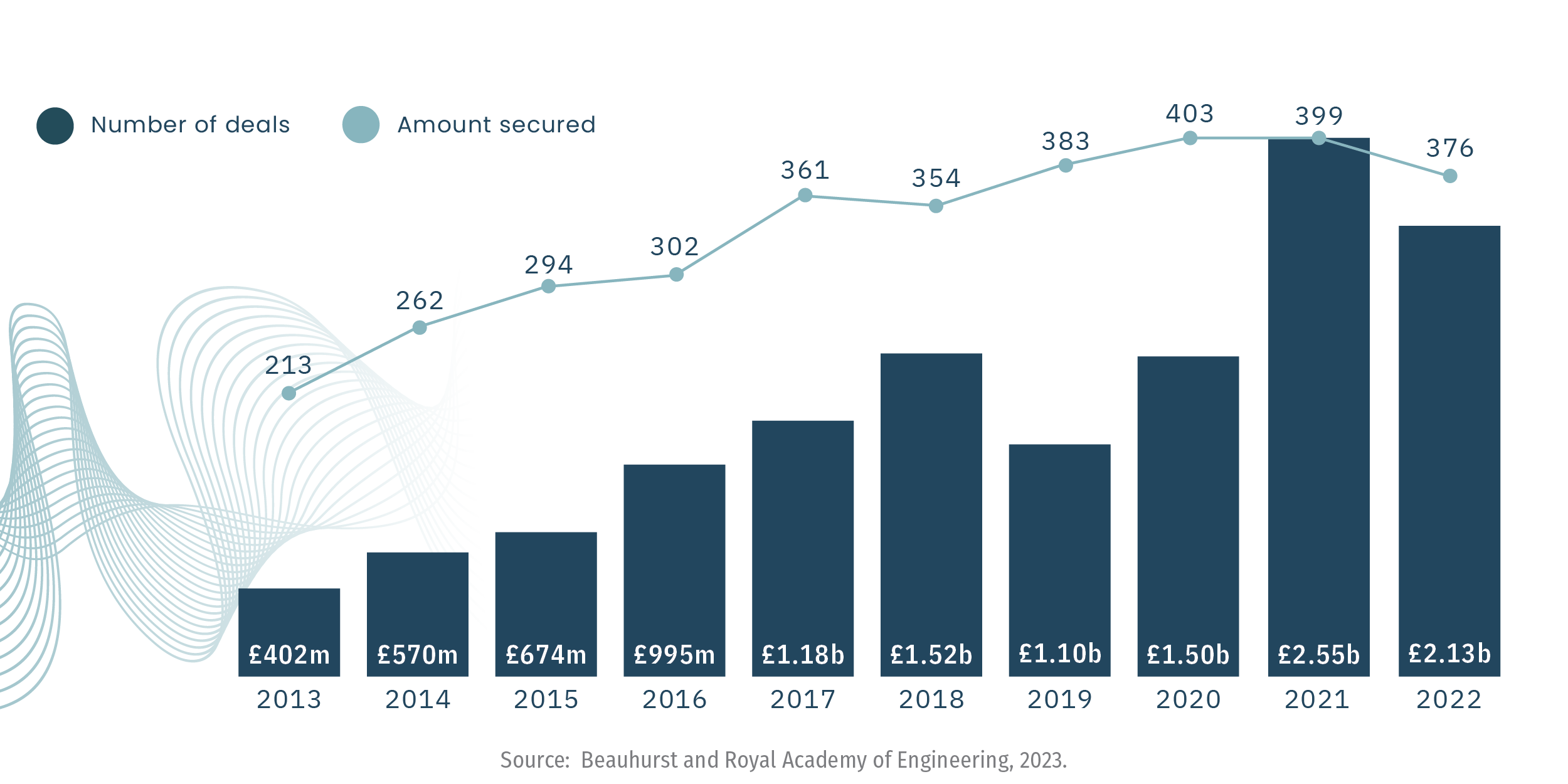

Equity Investment Secured by Spinouts in the UK

Since 2015, the TTO landscape in the UK evolved significantly. Increased government support, private investment interest, and strategic partnerships led to a notable increase in the number of spinouts: from the academic year 2014/15 to 2022/23, the number of active spinouts established at universities increased by 70%, with an average of more than 4,300 firms registered each year (Universities UK, 2025). Equity investment secured by spinouts also increased dramatically, rising from £402 million in 2013 to £2.55 billion in 2021 and £2.13 billion in 2022 (Beauhurst and Royal Academy of Engineering, 2023). Recognising the economic potential of commercialising research discoveries, universities are continuing to invest considerably in their TTOs. They are adopting best practices for patent and other IP protection from industry, hiring licensing experts from the private sector, and building business development teams.

Understanding this sector’s evolution is critical to exploring the opportunities and challenges it faces today. Some TTOs at UK universities may be hindered by their heritage. Their historical status and traditional role as facilitators for licensing can impede their transition to a spinout-first model, in part due to assumptions held by university leadership regarding roles, capabilities, and risks. That said, some technologies are better suited to licensing than a spinout route, and outsized incentives for startups can lead to research being commercialised in a less opportune way. Additionally, an overemphasis on spinouts can result in a talent drain of star scientists from academia, as they may be drawn away from their research and teaching responsibilities to focus on entrepreneurial ventures, potentially diminishing the university’s research capabilities and academic output. While these evolutionary challenges are significant, they are compounded by broader structural issues that define the current juncture in UK tech transfer.

Pivotal Challenges and Barriers to Scale

Having successfully navigated through the early phases and built the foundations of an innovation ecosystem, the UK now faces the challenge of truly enhancing impact — moving beyond generating spinouts to creating an environment where these companies can scale, mature, and deliver their full economic and societal benefits within the UK. Two structural challenges stand as significant barriers to unlocking the full potential of the UK’s world-class research base:

The Golden Triangle Concentration

Perhaps the most visible challenge is the geographic concentration of tech transfer success within the Golden Triangle of Cambridge, London, and Oxford. While these regions have developed thriving innovation hubs, with robust support structures, much of the UK’s potential remains untapped. Areas outside the Golden Triangle often have fewer facilities and structures in place, requiring more upfront work for commercialisation.

Encouragingly, recent measurements of spinout activity per UK local authority show notable growth in several regions outside the Golden Triangle, particularly in Edinburgh, Manchester, Belfast, Glasgow, and Bristol (Beauhurst and Royal Academy of Engineering, 2023). To capitalise on this potential, it is essential to implement robust structures to promote development in these regions and invest in broader innovation hubs to support startups through facilities, capital, incubation, and manufacturing capabilities. Without such investment, the current trend of promising startups relocating to the Golden Triangle or the US will continue, further concentrating innovation rather than distributing its economic benefits across the UK.

The Incubator Economy Risk

A concerning trend is the UK’s potential transformation into what some experts call an “incubator economy.” In this scenario, the UK excels at generating innovative spinouts but lacks both the supportive business climate and mature corporate ecosystem needed for these companies to scale and mature domestically. The absence of significant UK-based industry consolidators means many ventures leave the country or are acquired by international competitors before reaching their full potential. Without homegrown consolidators and a business environment conducive to scaling, most of the economic value is captured elsewhere.

Recent reports highlight this trend, citing a lack of funding for scaling as a primary factor (Universities UK, 2025). While the UK has made significant progress in early-stage funding, the absence of late-stage growth capital, along with talent and infrastructure gaps, forces rising startups to relocate to the US or seek early acquisition by international competitors.

The implications of these challenges extend beyond individual universities or ventures — they affect the UK’s capacity to fully leverage its exceptional research base and generate long-lasting economic and societal impact. Addressing these issues likely requires thoughtful consideration of how the UK might evolve its approach to university research commercialisation, building on existing strengths while developing new capabilities.

Risk, Resources, and Returns: Lessons from a Mature US Tech Transfer Ecosystem

At this critical juncture in the UK tech transfer sector’s development, examining alternative models can provide constructive insights. The more mature tech transfer landscape in the United States offers particularly relevant perspectives — not as a blueprint to be copied wholesale, but as a source of important lessons in scaling innovations, developing talent, and creating sustainable funding models that can be adapted to the UK’s unique context.

The US established itself as a world leader in tech transfer, amplified by its economic scale, infrastructure, funding, and entrepreneurial culture. Over 1,000 new university-associated startups were created in the US in 2021 (compared to nearly 400 in 2000), and US universities executed about 8,800 new technology licenses or options that same year. Over a 25-year period, academic-industry partnerships contributed $1.9 trillion to US gross output and $1 trillion to GDP and supported the creation of 6.5 million jobs (Biotechnology Innovation Organisation and AUTM, 2022).

Financial Foundations

American universities benefit from substantial financial resources that enable higher risk tolerance in tech transfer activities. Rather than relying primarily on endowments that largely support student financial aid and core academic functions (NACUBO, 2025), US institutions developed dedicated innovation funds, university-affiliated venture funds, and strategic partnerships with industry investors. These specialised financial structures provide the capital cushion for universities to pursue more ambitious commercialisation strategies.

The US system also benefitted from more diverse funding sources, including robust federal research grants specifically designed to bridge the “valley of death” between discovery and commercialisation, state-level innovation initiatives, and philanthropic contributions targeted at entrepreneurship. This multi-layered funding framework creates financial stability, allowing TTOs to take calculated risks on early-stage technologies with longer development timelines.

Structural Support for Scaling-up

The US ecosystem provides robust structural support for scaling spinout companies through several key mechanisms that work in concert to facilitate growth. Specialised venture capital firms with deep sector expertise offer not just funding but strategic guidance tailored to specific industries. For example, life sciences-focused venture capital firms often include former biotech executives who understand the unique challenges of therapeutic development.

Manufacturing and prototyping facilities, particularly in hubs like Massachusetts and California, allow companies to rapidly iterate on designs and scale production without massive capital investments. The regulatory navigation support available through specialised consultancies and university partnerships helps spinouts navigate complex approval processes, particularly in regulated industries like life sciences. Perhaps most critically, the longer history of innovation-commercialisation cycles established a deeper talent pipeline of executive leadership experienced in growing companies.

Increased government funding for tech transfer in the UK has not been matched with investment in these key scale-up infrastructure components. A lack of manufacturing capabilities, talented C-suite level talent with relevant experience, and risk capital for early-stage companies means that many promising UK startups move operations to the US to take advantage of increased resources and capabilities in these areas.

Entrepreneurial Culture

Our conversations with tech transfer executives revealed how UK spinout culture is less ambitious compared to the US, particularly its hubs in Silicon Valley and Cambridge, Massachusetts, citing a lack of networks and connections and a focus on short-term deliverables from funding bodies. The broader UK culture around entrepreneurship and success is significantly different from that in the US, the latter of which has been fortified by innumerable success stories and the widespread cultural impact of Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley’s “move fast and break things” culture promotes the risk-taking needed for startup success — a culture that needs to be reconciled with the deeply scientific nature of many university spinouts cultivated on a more measured approach, rooted in long-term objectives.

The McMillan Group’s 2016 review highlighted how these cultural differences are reinforced by structural factors, including greater public and private investment in the US, more direct routes to impact, and a longstanding focus in national policies on entrepreneurship and tech transfer (McMillan Group, 2016). However, senior stakeholders from across the UK tech transfer landscape emphasize that the goal should not be to replicate the US model, but rather to adapt certain components — namely, a higher risk tolerance, increased development funding, and more efficient structures — while respecting the UK’s distinctive characteristics. These include regulatory frameworks, institutional structures, regional innovation dynamics, and the established relationships between universities and their local communities. This balanced approach acknowledges both the lessons to be learned from the US experience and the significance of developing UK-focused solutions to the challenges of scaling university innovations.

Cultivating Leadership: Building the Talent Pipeline for UK Tech Transfer

With this understanding of both the UK’s challenges and the US’s strengths, we now turn to what may be the most critical factor in determining the future path of UK tech transfer: leadership development. Cultivating the right talent — particularly leaders who can navigate the complex journey from academic discovery to commercial scale — is at the heart of the UK’s prospective evolution from an excellent incubator of ideas to a complete innovation ecosystem capable of nurturing companies through their entire lifecycle.

The Current Talent Landscape

Through extensive interviews with tech transfer leaders across the UK, a consistent picture emerges of a sector facing talent constraints that limit its potential. Despite impressive scientific capabilities, the leaders needed to commercialise these innovations remain in short supply.

Significant gaps in qualified talent. UK TTOs struggle to recruit the leaders needed to develop and scale university spinouts. Notably, there is a shortage of leaders with commercial experience, venture capital, and fundraising expertise, and particularly commercial leaders in cell and gene therapy, small molecules, diagnostics, and medical devices.

Reliance on and preference for talent coming from the US. Leaders from the US, with its more mature commercialisation market, often bring broader and deeper experience in tech transfer, spinouts, deep tech, and life sciences. However, high talent demand in their home country and compensation mismatches make attracting this talent challenging. In particular, the more established US research commercialisation sector relies heavily on serial startup expertise in specific stages of a company’s development. Such CEOs and other executive leaders bring rich networks of contacts, specific business acumen, and experience in executing value realisation strategies through partnerships, IPO, or M&A.

Lack of prioritisation for developing local talent. Alongside the challenges in attracting experienced talent from the US, importing this talent is not a long-term, sustainable strategy for dealing with the talent shortage. A reliance on imported talent resulted in a lack of talent development programmes during the initial phase of TTO development. Despite increased government funding and targeted bootcamp offerings over the past number of years, TTOs still often struggle to find sufficient numbers of academics who want to pursue commercialisation pathways.

Positive indicators for the future. There is a positive feeling that talent may return to the UK in the coming years, driven by generational cultural shifts. Tech transfer leaders are hopeful that the coming years could witness a return of experienced biotech researchers and executives to the UK, alleviating the current talent shortage. Furthermore, the newest generation of academics demonstrates a strong entrepreneurial mindset and eagerness to engage in tech transfer, providing a positive outlook for the sector over the coming decades.

Accelerating the Future Through Impactful Leadership

Conversations across the ecosystem underscore that achieving the UK’s goals for increasing spinout activity is contingent upon securing fit-for-purpose talent. The following recommendations, reflecting our deep expertise in the field, aim to help leaders across the tech transfer sector — at universities, in industry, or in venture capital — navigate this evolving landscape, address current challenges, and capitalise on the opportunities impactful leadership can provide to this critical domain.

Cultivate a domestic talent pool. Imported talent, particularly from the US, has been essential in developing the UK’s tech transfer community and will continue to play an important role in dealing with the current talent shortage. However, UK TTOs should collaborate in prioritising far-reaching strategies to grow their own local talent pool. Initiatives focused on nurturing emerging skills and fostering a culture that encourages innovation, entrepreneurship, and calculated risk-taking will begin to develop the new generation of skilled and experienced tech transfer leaders. The fundamental requirements to achieve this include dedicated mentorship programmes, formal training pathways that combine scientific and commercial expertise, and recognition systems that celebrate commercialisation success alongside academic achievement.

Facilitate talent mobility. Fluid boundaries are needed to encourage talent to move across the continuum of innovation — between academia, industry, and spinout investment. This fosters collaboration, knowledge sharing, and mutually positive relationships across these intersecting industries and can help alleviate the talent shortage. This movement across the continuum is significantly less common in the UK than in the US.

Prioritise a milestone leadership approach. Finding effective leaders in this space presents unique difficulties, considering a broad and deep skillset needed across commercial, fundraising, and scientific domains. Adopting a milestone leadership approach, which promotes tailoring different executive team structures, role mandates, and leader phenotypes across a company’s lifecycle, can provide an effective method for dealing with the leadership shortage through engaging leaders who hold the most relevant skillset at each stage of the company’s growth cycle. This approach also accelerates the velocity of repeat entrepreneurism, allowing talented researchers to leverage their strengths, continue their scientific work, and serially found new companies centred on emerging innovations. They feel compensated, rewarded, and recognised for what they do best, creating a renewable cycle of innovation.

Develop a network of commercial leaders. To support the milestone leadership approach, tech transfer offices should focus on developing a network of leaders with experience in life sciences and venture capital-backed businesses, ensuring a reliable pool of talent for deployment. TTOs should cultivate their relationships with industry and investors beyond financing and strategic partnership to facilitate talent movement, looking for talent across the entire value chain of innovation that can bring specific skills to support companies at various stages of growth.

Attracting successful UK entrepreneurs back from overseas markets could be achieved through targeted incentives, building on existing mechanisms such as government loans, Business Asset Disposal Relief (former Entrepreneurs’ Relief), Research and Development (R&D) Tax Credits, Patent Box, and others. Financial incentives, combined with entrepreneur-in-residence programmes and supportive infrastructures like incubators and accelerators, could create a compelling proposition for returnee talent.

Advocate for policy and structural changes. Advocate for policy and structural changes. Alongside specific initiatives aimed at attracting and developing talent, TTOs must continue to campaign and advocate for improvements in the structural, policy, and resource landscape. Building on the returnee talent strategies mentioned above, this should include supporting enhanced immigration pathways for international commercial leaders and scientific entrepreneurs. Equally important is creating a more ambitious and supportive culture for spinouts — one that rewards risk, innovation, and ambition in commercialisation — which will provide the necessary conditions to foster the next generation of leaders. These leaders will be essential to propel the UK tech transfer architecture to its next phase of development as it becomes increasingly integrated with university research activities.

From Potential to Powerhouse

The UK tech transfer sector stands at a pivotal moment in its evolution. Having successfully established the foundations of innovation infrastructure and dramatically increased spinout activity over the past decade, the UK now faces the challenge of maturing beyond an incubator of ideas to become a complete innovation ecosystem capable of scaling companies to their full potential.

The concentration of success within the Golden Triangle, the risk of becoming merely an incubator economy, and persistent talent gaps threaten to limit the full impact of the UK’s world-class research base. Our examination of the US tech transfer framework reveals important lessons that can be adapted — not copied — to the UK context, providing a roadmap for stakeholders to navigate the challenges ahead.

The talent gap emerges as perhaps the most pressing challenge — but also the greatest opportunity. By cultivating a domestic talent pool, facilitating mobility across the innovation continuum, adopting milestone leadership approaches, and developing stronger networks of commercial leaders, the UK can build the leadership capacity needed to drive the next phase of tech transfer evolution. The newest generation of academics, with their entrepreneurial mindset, offers particular cause for optimism.

The path forward requires bold vision, strategic investment, and above all, a commitment to developing the leaders who will guide the UK tech transfer sector through its next phase of enhanced impact.